Rhinoplasty (Nose job)

The document Rhinoplasty (Nose job) explores the intricacies of undergoing rhinoplasty in Turkey. This comprehensive guide delves into the various aspects of the procedure, highlighting its benefits and considerations. With a focus on providing detailed insights, it serves as a valuable resource for individuals considering rhinoplasty in Turkey, Dr. Gorkem Atsal.

What is Rhinoplasty?

Rhinoplasty, from Ancient Greek ῥίς (rhís), meaning “nose”, and πλαστός (plastós), meaning “moulded”, commonly called nose job, medically called nasal reconstruction, is a plastic surgery procedure for altering and reconstructing the nose.[1] Rhinoplasty may remove a bump, narrow nostril width, change the angle between the nose and the mouth, or address injuries, birth defects, or other problems that affect breathing, such as a deviated nasal septum or a sinus condition. Surgery only on the septum is called a septoplasty.

In closed rhinoplasty and open rhinoplasty surgeries – a plastic surgeon, an otolaryngologist (ear, nose, and throat specialist), or an oral and maxillofacial surgeon (jaw, face, and neck specialist), creates a functional, aesthetic, and facially proportionate nose by separating the nasal skin and the soft tissues from the nasal framework, altering them as required for form and function, suturing the incisions, using tissue glue and applying either a package or a stent, or both, to immobilize the altered nose to ensure the proper healing of the surgical incision.

History

![Plates vi & vii of the Edwin Smith Papyrus at the Rare Book Room, New York Academy of Medicine[3]](https://gorkematsal.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Picture-2.jpg)

Plates vi & vii of the Edwin Smith Papyrus at the Rare Book Room, New York Academy of Medicine[3]

Treatments for the plastic repair of a broken nose are first mentioned in the Edwin Smith Papyrus,[2] a transcription of text dated to the Old Kingdom from 3000 to 2500 BCE.[3]

The Ebers Papyrus (c. 1550 BC), an Ancient Egyptian medical papyrus, describes rhinoplasty as the plastic surgical operation for reconstructing a nose destroyed by rhinectomy. Such a mutilation was inflicted as a criminal, religious, political, and military punishment in that time and culture.[4]

Rhinoplasty techniques are described in the ancient Indian text Sushruta samhita by Sushruta, where a nose is reconstructed by using a flap of skin from the cheek.[5]

During the Roman Empire (27 BC – 476 AD) the encyclopaedist Aulus Cornelius Celsus (c. 25 BC – 50 AD) published the 8-tome De Medicina (On Medicine, c. 14 AD), which described plastic surgery techniques and procedures for the correction and the reconstruction of the nose and other body parts.[6]

In Italy, Gasparo Tagliacozzi (1546–1599), professor of surgery and anatomy at the University of Bologna, published Curtorum Chirurgia Per Insitionem (The Surgery of Defects by Implantations, 1597), a technico–procedural manual for the surgical repair and reconstruction of facial wounds in soldiers.

In Great Britain, Joseph Constantine Carpue (1764–1846) published the descriptions of two rhinoplasties: the reconstruction of a battle-wounded nose, and the repair of an arsenic-damaged nose. (cf. Carpue’s operation).[7,8]

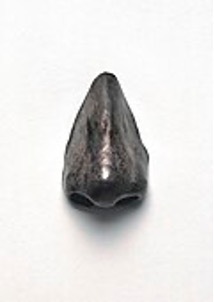

Artificial nose, made of plated metal, 17th–18th century Europe. This would have been worn as an alternative to rhinoplasty.

In Germany, rhinoplastic technique was refined by surgeons such as the Berlin University professor of surgery Karl Ferdinand von Gräfe (1787–1840), who published Rhinoplastik (Rebuilding the Nose, 1818) wherein he described 55 historical plastic surgery procedures, and his technically innovative free-graft nasal reconstruction (with a tissue-flap harvested from the patient’s arm), and surgical approaches to eyelid, cleft lip, and cleft palate corrections.[9]

In the United States, in 1887, the otolaryngologist John Orlando Roe (1848–1915) performed the first modern endonasal rhinoplasty (closed rhinoplasty) in order to treat saddle nose deformities.[10,11]

In the early 20th century, Freer, in 1902, and Killian, in 1904, pioneered the submucous resection septoplasty (SMR) procedure for correcting a deviated septum; they raised mucoperichondrial tissue flaps, and resected the cartilaginous and bony septum (including the vomer bone and the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid bone), maintaining septal support with a 1.0-cm margin at the dorsum and a 1.0-cm margin at the caudad. [12] In 1947, Maurice H. Cottle (1898–1981) endonasally resolved a septal deviation with a minimalist hemitransfixion incision, which conserved the septum; thus, he advocated for the practical primacy of the closed rhinoplasty approach.[4]

The endonasal rhinoplasty was the usual approach to nose surgery until the 1970s, when Padovan presented his technical refinements, advocating the open rhinoplasty approach; he was seconded by Wilfred S. Goodman in the later 1970s, and by Jack P. Gunter in the 1990s.[13,14] In 1987, Gunter reported the technical effectiveness of the open rhinoplasty approach for performing a secondary rhinoplasty; his improved techniques advanced the management of a failed nose surgery.[15]

Artificial nose, made of plated metal, 17th–18th century Europe. This would have been worn as an alternative to rhinoplasty.

Nasal analysis

The surgical management of nasal defects and deformities divides the nose into six anatomic subunits: (i) the dorsum, (ii) the sidewalls (paired), (iii) the hemilobules (paired), (iv) the soft triangles (paired), (v) the alae (paired), and (vi) the columella. [16]

The nasofrontal angle, intersection of the line from the nasion to the nasal tip with the line from the nasion to the glabella, usually is 115-130 degrees; the nasofrontal angle is more acute in the male face than in the female face. The nasofacial angle, intersection of the line from the nasion to the nasal tip with the line from the nasion to the pogonion, is approximately 30–40 degrees. The nasolabial angle, the slope between the columella and the philtrum, is approximately 90–95 degrees in the male face, and approximately 100–105 degrees in the female face. Therefore, when observing the nose in profile, the normal show of the columella (the height of the visible nasal aperture) is 2 mm; and the dorsum should be rectilinear (straight).

Patient characteristics

To determine the patient’s suitability for undergoing a rhinoplasty procedure, the surgeon clinically evaluates them with a complete medical history (anamnesis) to determine their physical and psychological health. The prospective patient must explain to the physician–surgeon the functional and aesthetic nasal problems that they have. The surgeon asks about the ailments’ symptoms and their duration, past surgical interventions, allergies, drugs use and drugs abuse (prescription and commercial medications), and a general medical history. Furthermore, additional to physical suitability is psychological suitability—the patient’s psychological motive for undergoing nose surgery is critical to the surgeon’s pre-operative evaluation of the patient.[4]

The complete physical examination of the rhinoplasty patient determines if he or she is physically fit to undergo and tolerate the physiologic stresses of nose surgery. The examination comprehends every existing physical problem, and a consultation with an anaesthesiologist, if warranted by the patient’s medical data. The external and internal nasal examination concentrates upon the anatomic thirds of the nose—upper section, middle section, lower section—specifically noting their structures; the measures of the nasal angles (at which the external nose projects from the face); and the physical characteristics of the naso-facial bony and soft tissues. The internal examination evaluates the condition of the nasal septum, the internal and external nasal valves, the turbinates, and the nasal lining, paying special attention to the structure and the form of the nasal dorsum and the tip of the nose.[4]

Surgical rhinoplasty

Open rhinoplasty versus closed rhinoplasty

Technically, the plastic surgeon’s incisional approach classifies the nasal surgery either as an open rhinoplasty or as a closed rhinoplasty procedure. In open rhinoplasty, the surgeon makes a small, irregular incision to the columella, the fleshy, exterior-end of the nasal septum; this columellar incision is additional to the usual set of incisions for a nasal correction. In closed rhinoplasty, the surgeon performs every procedural incision endonasally (exclusively within the nose), and does not cut the columella.[4]

The "ethnic nose"

The open rhinoplasty approach affords the plastic surgeon advantages of ease in securing grafts (skin, cartilage, bone) and, most importantly, in securing the nasal cartilage properly, and so better to make the appropriate assessment and remedy. This procedural aspect can be especially difficult in revision surgery, and in rhinoplastic alteration of the thick-skinned “ethnic nose” of the person of color.

Recently, ultrasonic rhinoplasty[17] which was introduced by Massimo Robiony in 2004 has become an alternative to traditional rhinoplasty.[18] Ultrasonic rhinoplasty uses piezoelectric instruments[19] to reshape atraumatically nasal bones, also known as rhinosculpture. Ultrasonic rhinoplasty uses piezoelectric instruments (scrapers rasps, saws) that affect only the bones and the stiff cartilages through ultrasonic vibrations, as the instruments used in dental surgery.[20] The use of piezoelectric instruments requires a more extended approach than the isial one, allowing to visualize the whole bony vault, to reshape it with rhinosculpture or to mobilize and stabilize bones after controlled osteotomies.[21]

At my clinic, I often recommend ultrasonic rhinoplasty because it allows me to reshape the nose with far more precision and care compared to traditional methods. Using a special ultrasonic device, I can sculpt the nasal bones without breaking them, which means less trauma to the surrounding tissues, reduced bruising, and a smoother recovery. This technique is especially helpful for patients who want refined results with minimal downtime. Every nose is unique, and with ultrasonic technology, I can work more delicately and accurately to achieve a natural, balanced look that truly suits the patient’s face.

Surgical procedure

A rhinoplastic correction can be performed on a person who is under sedation, under general anaesthesia, or under local anaesthesia; initially, a local anaesthetic mixture of lidocaine and epinephrine is injected to numb the area, and temporarily reduce vascularity, thereby limiting any bleeding. Generally, the plastic surgeon first separates the nasal skin and the soft tissues from the osseo–cartilagenous nasal framework, and then reshapes them, sutures the incisions, and applies either an external or an internal stent, and tape, to immobilize the newly reconstructed nose, and so facilitate the healing of the surgical cuts. Occasionally, the surgeon uses either an autologous cartilage graft or a bone graft, or both, in order to strengthen or to alter the nasal contour(s). The autologous grafts usually are harvested from the nasal septum, but, if it has insufficient cartilage (as can occur in a revision rhinoplasty), then either a costal cartilage graft (from the rib cage) or an auricular cartilage graft (concha from the ear) is harvested from the patient’s body. Homologous (donor) rib cartilage is also sometimes used if the patient’s own cartilage is unsuitable.[22,23]

In plastic surgical praxis, the term primary rhinoplasty denotes an initial (first-time) reconstructive, functional, or aesthetic corrective procedure. The term secondary rhinoplasty denotes the revision of a failed rhinoplasty, an occurrence in 5–20 per cent of rhinoplasty operations, hence a revision rhinoplasty. The corrections usual to secondary rhinoplasty include the cosmetic reshaping of the nose because of a functional breathing deficit from an over aggressive rhinoplasty, asymmetry, deviated or crooked nose, areas of collapses, hanging columella, pinched tip, scooped nose and more. Most revision rhinoplasty procedures are repaired with “open approach”, such a correction is more technically complicated, usually because the nasal support structures either were deformed or destroyed in the primary rhinoplasty; thus the surgeon must re-create the nasal support with cartilage grafts harvested either from the ear (auricular cartilage graft) or from the rib cage (costal cartilage graft).

A functional rhinoplasty refers to a rhinoplasty performed to alleviate nasal obstruction, whereas a cosmetic rhinoplasty refers to a rhinoplasty performed for aesthetic reasons. Procedures performed as part of a functional rhinoplasty typically include septoplasty, inferior turbinate reduction, and spreader graft placement.

Results

Can be good if performed by an experienced practitioner. As in all plastic surgery procedures, there can be some unpredictability, and biologic systems can heal in different ways.

Post–surgical recovery

Convalescence

The rhinoplasty patient returns home after surgery, to rest, and allow the nasal cartilage and bone tissues to heal the effects of having been forcefully cut. Assisted with prescribed medications—antibiotics, analgesics, steroids—to alleviate pain and aid wound healing, the patient convalesces for about 1-week, and can go outdoors. Post-operatively, external sutures are removed at 4–5 days; the external cast is removed at 1-week; the stents are removed within 4–14 days; and the “panda eyes” periorbital bruising heal at 2-weeks. If an alar base reduction is performed conjunctively within the Rhinoplasty, these sutures need to be removed within 7–10 days post operatively. Throughout the first year post-operative, in the course of the rhinoplastic wounds healing, the tissues will shift moderately as they settle into being a new nose. Furthermore, as rhinoplasty climbs the ladder of surgical procedures performed to achieve an aspired appearance, especially amongst women, the relationship between body image and mental state must be examined in order to destigmatize motives behind the surgical intervention.[24,25]

Risk

Rhinoplasty is safe, yet complications can arise; post-operative bleeding is uncommon, but usually resolves without treatment. Infection is rare, but, when it does occur, it might progress to become an abscess requiring the surgical drainage of the pus, whilst the patient is under general anaesthesia. Adhesions, scars that obstruct the airways, can form a bridge across the nasal cavity, from the septum to the turbinates, and lead to difficulty breathing and may require surgical removal. If too much of the osseo-cartilaginous framework is removed, the consequent weakening can cause the external nasal skin to become shapeless, resulting in a “polly beak” deformity, resembling the beak of a parrot. Likewise, if the septum is unsupported, the bridge of the nose can sink, resulting in a “saddle nose” deformity. The tip of the nose can be over-rotated, causing the nostrils to be too visible, resulting in a porcine nose. If the cartilages of the nose tip are over-resected, it can cause a pinched-tip nose. If the columella is incorrectly cut, variable-degree numbness might result, which requires a months-long resolution. Other deformities that may result from a rhinoplasty include Rocker deformity, inverted V deformity, and open room deformity.[26] Furthermore, in the course of the rhinoplasty, the surgeon might accidentally perforate the septum (septal perforation), which later can cause chronic nose bleeding, crusting of nasal fluids, difficult breathing, and whistling breathing. A turbinectomy may result in empty nose syndrome.

Non-surgical rhinoplasty

Non-surgical rhinoplasty is a medical procedure in which injectable fillers, such as collagen or hyaluronic acid, are used to alter and shape a person’s nose without invasive surgery. The procedure fills in depressed areas on the nose, lifting the angle of the tip or smoothing the appearance of bumps on the bridge.[27]

References

.Fischer, Helmut; Gubisch, Wolfgang (24 October 2008). “Nasal Reconstruction”. Deutsches Ärzteblatt International. 105 (43): 741–746. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2008.0741. ISSN 1866-0452. PMC 2696977. PMID 19623298.

2.Shiffman, Melvin (2012-09-05). Cosmetic Surgery: Art and Techniques. Springer. p. 20. ISBN 978-3-642-21837-8.

3.Mazzola, Ricardo F.; Mazzola, Isabella C. (2012-09-05). “History of reconstructive and aesthetic surgery”. In Neligan, Peter C.; Gurtner, Geoffrey C. (eds.). Plastic Surgery: Principles. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 11–12. ISBN 978-1-4557-1052-2.

5.Melvin A. Shiffman, Alberto Di Gi. Advanced Aesthetic Rhinoplasty: Art, Science, and New Clinical Techniques. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 132.

6.Chernow BA, Vallasi GA, eds. (1993). The Columbia Encyclopedia (5th ed.). Columbia University Press. pp. 488–9.

7.Rinzler, CA (2009). The Encyclopedia of Cosmetic and Plastic Surgery. New York NY: Facts on File. p. 151.

8.Muley G. Sushruta: Great Scientists of ancient India. URL: http://www.vigyanprasar.gov.in/dream/july2000.article.htm.Accessed[permanent dead link] on 07/07/2007 (s)

9.Goldwyn RM (July 1968). “Johann Friedrich Dieffenbach (1794–1847)”. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 42 (1): 19–28. doi:10.1097/00006534-196842010-00004. PMID 4875688.

10.Roe JO. “The Deformity Termed ‘Pug Nose’ and its Correction, by a Simple Operation”. 31. New York: The Medical Record; 1887:621.

11.Rinzler 2009, pp. 151–2

12.Rethi A (1934). “Operation to Shorten an Excessively Long Nose”. Revue de Chirurgie Plastique. 2: 85.

13.Goodman WS, Charles DA (February 1978). “Technique of external rhinoplasty”. J Otolaryngol. 7 (1): 13–7. PMID 342721.

14.Gunter JP (March 1997). “The merits of the open approach in rhinoplasty”. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 99(3): 863–7. doi:10.1097/00006534-199703000-00040. PMID 9047209.

15.Gunter JP, Rohrich RJ (August 1987). “External Approach for Secondary Rhinoplasty”. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 80 (2): 161–174. doi:10.1097/00006534-198708000-00001. PMID 3602167. S2CID 10012520.

16.Burget GC, Menick FJ (August 1985). “The subunit principle in nasal reconstruction”. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 76 (2): 239–47. doi:10.1097/00006534-198508000-00010. PMID 4023097. S2CID 35516688.

17.“Ultrasonic bone surgery for more treatments secure and less traumatic” (PDF). Acteon Group.

18.Shah, Manish (14 May 2019). “What is an ultrasonic rhinoplasty?”. American Society of Plastic Surgeons. Retrieved 26 February 2020.

19.Daniel, Rollin K.; Pálházi, Péter (2018). Rhinoplasty: An Anatomical and Clinical Atlas. Springer. p. 138. ISBN 978-3-319-67314-1.

20.“Ultrasonic Rhinoplasty : A revolution for patients”. Invivox. 2017-05-22. Retrieved 2019-04-07.

21.Pribitkin, Edmund A.; Lavasani, Leela S.; Shindle, Carol; Greywoode, Jewel D. (2010). “Sonic rhinoplasty: sculpting the nasal dorsum with the ultrasonic bone aspirator”. The Laryngoscope. 120 (8): 1504–1507. doi:10.1002/lary.20980. ISSN 1531-4995. PMID 20564664. S2CID 46295767.

22.Luan CW, Chen MY, Yan AZ, Tsai YT, Hsieh MC, Yang HY, Chou HH (July 2022). “Complications associated with irradiated homologous costal cartilage use in rhinoplasty: A systematic review and meta-analysis”. Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive & Aesthetic Surgery. 75 (7): 2359–2367. doi:10.1016/j.bjps.2022.02.026. PMID 35354546.

23.Salzano G, Audino G, Dell’Aversana Orabona G, Committeri U, Troise S, Arena A, Vaira LA, De Luca P, Scarpa A, Elefante A, Romano A, Califano L, Piombino P (March 2024). “Fresh Frozen Homologous Rib Cartilage: A Narrative Review of a New Trend in Rhinoplasty”. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 13 (6): 1715. doi:10.3390/jcm13061715. PMC 10971137. PMID 38541940.

24.Bonell, Sarah; et al. (Sep 2021). “Under the knife: Unfavorable perceptions of women who seek plastic surgery”. ProQuest Central. ProQuest 2570021746. Retrieved 9 Dec 2024.

25.Ferreira, Thales Victor Fernandes; et al. (2025). “Importance of psychological follow-up in rhinoplasty”. Brazilian Journal of Otorhinolaryngology. 91. doi:10.1016/j.bjorl.2024.101498. PMC 11470162.

26.Raggio, Blake S.; Asaria, Jamil (2024), “Open Rhinoplasty”, StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 31536235, retrieved 2024-08-26

27.“History”. acmilan.com. Associazione Calcio Milan. Archived from the original on 7 October 2010. Retrieved 4 October 2010.