Otoplasty

Otoplasty, from Ancient Greek οὖς (oûs), meaning “ear”, and πλαστός (plastós), meaning “moulded”, is a procedure for correcting the deformities and defects of the auricle (external ear), whether these defects are congenital conditions (e.g. microtia, anotia, etc.) or caused by trauma.[1] Otoplastic surgeons may reshape, move, or augment the cartilaginous support framework of the auricle to correct these defects.

[1] Otoplastic surgeons may reshape, move, or augment the

cartilaginous support framework of the auricle to correct these defects.

History

Otoplasty was developed in ancient India and is described in the medical compendium,

the Sushruta Samhita (Sushruta’s Compendium, c. 500 AD). And plastic surgery

techniques of the Sushruta Samhita were practiced throughout Asia until the late 18th

century.

[2][3]

The German polymath Johann Friedrich Dieffenbach was a pioneer in the fields of plastic surgery. (c. 1840)

19th century

In Die operative Chirurgie (Operational Surgery, 1845), Johann Friedrich Dieffenbach

(1794–1847) reported the first surgical approach for the correction of prominent ears — a

combination otoplasty procedure that featured the simple excision (cutting) of the

problematic excess cartilage.[4][5]

20th and 21st centuries

In 1920, Harold D. Gillies (1882–1960) first reproduced the auricle by burying an external-

ear support framework, made of autologous rib cartilage, under the skin of the mastoid

region of the head, which reconstructed the auricle; he then separated this from the skin of

the mastoid area by means of a cervical flap.

In 1964, Radford C. Tanzer (1921–2004) re-emphasized the use of autologous cartilage as

the most advantageously reliable organic material for resolving microtia (abnormally small

ears), because of its great histologic viability, resistance to shrinkage, and resistance to

softening, and lower incidence of resorption.

The development of plastic surgery procedures, such as the refinement of J.F.

Dieffenbach’s ear surgery techniques, has established more than 170 otoplasty

procedures for correcting prominent ears, and for correcting defects and deformities of the

auricle; as such, otoplasty corrections are in three surgical-technique groups:

• Group I – Techniques that leave intact the cartilage support-framework of the ear, and

reconfigure the distance and the angle of projection of the auricle from the head, solely

by means of sutures, as in the permanent suture-insertion of the Mustardé technique[6]

the Merck stitch method[7] and the incisionless Fritsch otoplasty[8][9][10] for creating an anti

helical fold.

• Group II — Techniques that resect (cut and remove) the pertinent excess cartilage

from the support-framework of the auricle, which then render it pliable to being re-

molded, reconfigured, and affixed to the head at the projection distance-and-angle

characteristic of a normal ear; the relevant procedures are the cartilage-incision

Converse technique and the Chongchet–Stenström technique for the anterior-

correction of prominent ears.[11][12][13]

• Group III — Techniques that combine the excision of cartilage portions from the

support framework of the auricle, in order to reduce the degree of projection and the

distance of the external ear from the head.[14]

The auricle

The external ear (auricle) is a surgically challenging area in terms of anatomy, composed of

a delicate and complex framework of shaped cartilage that is covered, on its visible

surface, with thin, tightly adherent, hairless skin. Although of small area, the surface

anatomy of the external ear is complex, consisting of the auricle and the external auditory

meatus (auditory canal). The outer framework of the auricle is composed of the rim of the

helix, which arises from the front and from below (anteriorly and inferiorly), from a crus

(shank) that extends horizontally above the auditory canal. The helix merges downwards

(inferiorly) into the cauda helices (tail of the helix), and connects to the lobule (earlobe).

Prominent ears

In the practice of otoplasty, the term “prominent ears” describes external ears (auricles)

that, regardless of their size, protrude from the sides of the head. The abnormal

appearance exceeds the normal head-to-ear measures, wherein the external ear is less

than 2 cm (0.79 in), and at an angle of less than 25 degrees, from the side of the head. Ear

configurations, of distance and angle, that exceed the normal measures, appear

prominent when the man or the woman is viewed from either the front or the back

perspective. In the occurrence of prominent ears, the common causes of anatomic defect,

deformity, and abnormality can occur individually or in combination; they are:

1. Underdeveloped antihelical fold

This anatomic deformity occurs consequent to the inadequate folding of the

antihelix, which causes the protrusion of the scapha and the helical rim. The defect

is manifested by the prominence of the scapha (the elongated depression

separating the helix and the antihelix) and the upper-third of the ear; and

occasionally of the middle third of the ear.

2. Prominent concha

This deformity is caused either by an excessively deep concha, or by an excessively

wide concha-mastoid angle (<25 degrees). These two anatomic abnormalities can

occur in combination, and produce a prominent concha (the largest, deepest

concavity of the auricle), which then causes the prominence of the middle third of

the external ear.

3. Protruding earlobe

This defect of the earlobe causes the prominence of the lower third of the auricle.

Although most prominent ears are anatomically normal, morphologic defects, deformities,

and abnormalities do occur, such as the:

• Constricted ear

• Cryptotic ear

• Macrotic ear

• Question mark ear

• Stahl’s ear deformity

Angles of the ear

Cephaloauricular and scaphoconchal angles

The degrees of angle between the head and the ear, and the degrees of angle between the

scapha and the concha, determine the concept of prominent ears.

Antihelix

The antihelix normally forms a symmetric Y-shaped structure in which the gently rolled

(folded) crest of the root of the antihelix continues upwards as the superior crus, and the

inferior crus branches forwards, from the root, as a folded ridge.

Concha

The concha of the ear is an irregular hemispheric bowl with a defined rim. The normal

scapha–helix surrounds the posterior part of the bowl (much as the brim of an inverted hat

surrounds the crown).

If the posterior wall of the concha is excessively high, and the concha is excessively

spherical, then there is an excessive angle and distance between the plane of the scapha–

helix and the plane of the temporal surface of the head, another cause for a protruding ear.

The concha affects the prominence of the ear three-fold ways:

1. The overall enlargement of the concha projects the ear away from the mastoid

surface;

2. An extension of the helical crus across the concha creates a firm cartilage bar that

pushes the ear outwards

3. The effect of the angulation of the cartilage, at the junction between the cavum

concha; and the sweep of cartilage up to the antitragal prominence, affects the

position and prominence of the lobule (earlobe) and lower third of the ear.

Protruding antihelix and protruding concha combined

The combined effects of an effaced antihelix and a deep concha also contribute to severe

auricular protrusion (a very prominent ear).

Hemifacial microsomia:

The undersized development of one side of a person’s face,

demonstrates the influence of skeletal development upon the position of the external ear

on the head, as caused by the deficient morphologic development of the temporal bone,

and by the medial positioning of the temporomandibular joint, the synovial joint between

the temporal bone and the mandible (upper jaw). Moreover, in severe cases of hemifacial

microsomia, without the occurrence of microtia (small ears), the normal external ear mightappear to have been sheared off the head, because the upper half of the auricle is

projecting outwards, and, at the middle point, the lower half of the auricle is canted

inwards, towards the hypoplastic, underdeveloped side of the face of the patient.

Protruding cauda helicis

Protruding earlobe

Soft tissues

Surgical otoplasty

The corrective goal of otoplasty is to set back the ears so that they appear naturally

proportionate and contoured without evidence or indication of surgical correction.

Therefore, when the corrected ears are viewed, they should appear normal, from the:

1. Front perspective: when the ear (auricle) is viewed from the front, the helical rim

should be visible, but not set back so far (flattened) that it is hidden behind the

antihelical fold.

2. Rear perspective: when the auricle is viewed from behind, the helical rim is straight,

not bent, as if resembling the letter ‘C’ (the middle-third to flat), or crooked, as if

resembling a hockey stick (the earlobe is insufficiently flat). If the helical rim is

straight, the upper-, middle-, and lower-thirds of the auricle will be proportionately

setback in relation to each other.

3. Side perspective: the contours of the ear should be soft and natural, not sharp and

artificial.

The severity of the ear deformity that is to be corrected determines the advantageous

timing of an otoplasty; for example, in children with extremely prominent ears, 4 years old

is a reasonable age. [15]

Surgical procedures

Otoplastic surgery can be performed upon a patient under anesthesia — local anesthesia,

local anesthesia with sedation, or general anesthesia (usual for children).

Surgical otoplasty techniques

Depending upon the auricular defect, deformity, or reconstruction required, the surgeon

applies these three otoplastic techniques, either individually or in combination to achieve

an outcome that produces an ear of natural proportions, contour, and appearance:

Antihelical fold manipulation

▪ Suturing of the cartilage: the surgeon emplaces mattress sutures on

the back of the ears, which are tied with sufficient tension to increase

the definition of the antihelical fold, thereby setting back the helical

rim. The cartilage is not treated. This is the technique of Mustardé[6]

and Merck[7]

.

▪ Stenström technique of anterior abrasion: the abrasion (roughening

or scoring) of the anterior (front) surface of the anti helical fold

cartilage causes the cartilage to bend away from the abraded side

(per the Gibson principle), towards the side of intact perichondrium,

the membrane of fibrous connective tissue.

▪ Full-thickness incisions: one full-thickness incision along the

desired curvature of the antihelix permits folding it with slight force,

thereby creating an antihelical fold (as in the Luckett procedure). Yet,

because such a fold is sharp and unnatural in appearance, the

technique was modified as the Converse–Wood-Smith technique,

wherein two incisions are made, running parallel to the desired

antihelical fold, and tubing sutures are emplaced to create a more

defined fold of natural contour and appearance.

• Conchal alteration

▪ Suturing: the surgeon decreases the angle (-25 degrees) between the

concha and the mastoid process of the head with sutures emplaced

between the concha and the mastoid fascia.[16]

▪ Conchal excision: from either an anterior or a posterior approach,

the surgeon removes a full-thickness crescent of cartilage from the

posterior wall of the concha (ascertaining to neither violate nor

deform the antihelical fold), to thereby reduce the height of the

concha.

▪ Combination of suturing and conchal excision: The surgeon applies

a corrective technique that combines the pertinent technical aspects

of the Furnas suture technique and of the conchal excision

techniques.

Types of otoplastic correction

Ear augmentation,

addressing microtia (underdeveloped auricle) and anotia (absent

auricle) involves adding structural elements to replace the missing structures with

cartilage tissue grafts harvested either from the ear (auricular cartilage) or from the rib

cage (costal cartilage).

Ear pinback

An otopexy that “flattens” protuberant ears against the head (15–18

millimetres (0.59–0.71 in)).[3]

Ear reduction

addressing macrotia, might involve reducing one or more of the

components of oversized ears; the incisions usually are hidden in, or near, the front

folds of the auricle.

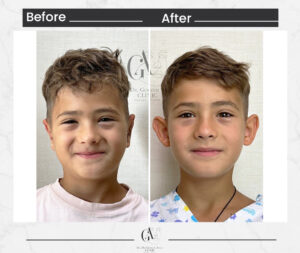

At my clinic here in Istanbul, I perform otoplasty with great attention to detail, focusing on creating a natural, symmetrical result that suits each individual’s facial structure. Whether the goal is to correct prominent ears or simply achieve better balance, otoplasty in Turkey has become a trusted option for many international patients thanks to our high standards and personalized care. I’m personally involved in every step of the journey—from the first consultation to the final result—to make sure each patient feels safe, heard, and confident. If you’re thinking about ear surgery, I’d be happy to welcome you to my clinic and show you the level of dedication and expertise we bring to every case. — Dr. Görkem Atsal

Post-surgical recovery

The internal structures, surgical wound or wounds can be sutured with either absorbable

sutures or with non-absorbable sutures that the plastic surgeon removes when the

surgical wound has healed. Depending upon the deformity to be corrected, the otoplasty

can be performed either as an outpatient surgery or at hospital; while the operating room

time varies between 1 and 1.5 hour.

For several days after the surgery, the otoplasty patient wears a voluminous, non-

compressive dressing upon the corrected ear(s), and must avoid excessive bandage

pressure upon the ear during the convalescent period, lest it cause pain and increased

swelling, which might lead to the abrasion, or even to the necrosis of the ear’s skin. After

removing the dressing, the patient then wears a loose headband for a 4–8-week period; it

should be snug, not tight, because its purpose is preventing the corrected ear(s) from being

pulled forward, when the sleeping patient moves whilst asleep. An overly-tight headband

can abrade and erode the side surface of the ear, possibly creating an open wound.[17]

Complications

Hematoma:

a hematoma can be immediately addressed if the patient complains of

excessive pain, or when the surgical wound bleeds. The dressing is immediately

removed from the ear to ascertain the existence of a hematoma, which then isimmediately evacuated. If the surgical wound is infected, antibiotic therapy helps avoid

the occurrence either of abscess or of perichondritis (inflammation).

Infection:

cellulitis is rare after otoplasty, but it is treated aggressively, with antibiotics

in order to avoid chondritis, a condition potentially requiring debridement, and which

may permanently disfigure the ear.

Suture complications:

suture extrusion in the retroauricular sulcus (the groove behind

the ear) is the most common otoplastic complication following corrective surgery.

Such extruded sutures are easy to remove, but the extrusion occurrence might be

associated with granulomas, which are painful and unattractive. This complication

might be avoided by using absorbable sutures; to which effect, monofilament sutures

are likelier to protrude, but have a lesser incidence rate of granulomas, whereas

braided sutures are unlikely to protrude, but have a greater incidence rate of

granulomas.

Overcorrection and unnatural contour:

the most common, but significant,

complication of otoplasty is overcorrection, which can be minimized by the surgeon’s

detailed attention to the functional principles of the surgical technique employed.

Hence, function over form minimizes the creation of the unnatural contours

characteristic of the “technically perfect ear”.

Incidence of ear deformity

Approximately 20–30 per cent of newborn children are born with deformities of the external

ear (auricle) that can occur either in utero (congenitally) or in the birth canal (acquired). The

possible defects and deformities include protuberant ears (“bat ears”); pointed ears (“elfin

ears”); helical rim deformity, wherein the superior portion of the ear lacks curvature;

cauliflower ear, which appears as if crushed; lop ear, wherein the upper portion of the

auricle is folded onto itself; and others. Such deformities usually are self-correcting, but, if

at 1 week of age, the child’s external ear deformity has not self-corrected, then either

surgical correction (otoplasty 5–6 years of age) or non-surgical correction (tissue molding)

is required to achieve an ear of normal proportions, contour, and appearance.

Non-surgical otoplasty: the therapeutic aspects, before (left), during (center), and after (right), of a

tissue-molding procedure performed with an EarWell device.If detected early, Infant’s ear molding can

permanently correct ear shape without the need for surgery. However, if ear deformities go unnoticed or

untreated during infancy, surgical otoplasty might be considered later in childhood to achieve long-

lasting results.[18]

Tissue molding

In the early weeks of infancy, the cartilage of the infantile auricle is unusually malleable,

because of the remaining maternal estrogens circulating in the organism of the child.

During that biochemically privileged period, prominent ears, and related deformities, can

be permanently corrected by molding the auricles (ears) to the correct shape, either by the

traditional method of taping, with tape and soft dental compound (e.g. gutta-percha latex),

or solely with tape; or with non-surgical tissue-molding appliances, such as custom-made,

defect-specific splints designed by the physician. Therapeutically, the splint-and-

adhesive-tape treatment regimen is months-long, and continues until achieving the

desired outcome, or until there is no further improvement in the contour of the auricle,

likewise, with the custom and commercial tissue-molding devices.[17]

Taping

The traditional, non-surgical correction of protuberant ears is taping them to the head of

the child, in order to “flatten” them into the normal configuration. The physician effects this

immediate correction to take advantage of the maternal estrogen-induced malleability of

the infantile ear cartilages during the first 6 weeks of their life. The taping approach can

involve either adhesive tape and a splinting material, or only adhesive tape; the specific

deformity determines the correction method. This non-surgical correction period is

limited, because the extant maternal estrogens in the child’s organism diminish within 6–8

weeks; afterwards, the ear cartilages stiffen, thus, taping the ears is effective only for

correcting “bat ears” (prominent ears), and not the serious deformities that require surgical

re-molding of the auricle to produce an ear of normal size, contour, and proportions.

Furthermore, ear correction by splints and tape requires the regular replacement of the

splints and the tape, and especial attention to the child’s head for any type of skin erosion,

because of the cumulative effects of the mechanical pressures of the splints proper and

the adhesive of the fastener tape.

Physician-designed splints

A study, Postpartum Splinting of Ear Deformities (2005), reported the efficacy of physician-

designed splinting the ears of a child during the early neonatal period as a safe and

effective non-surgical treatment for correcting congenital ear deformities.[19]

REFERENCES

1.Onions CT, editor (1996) The Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology. Oxford University Press

p. 635.

2.Wujastyk, Dominik, ed. (2003). The roots of Ayurveda: selections from Sanskrit medical

writings. Penguin classics (Rev. ed.). London: Penguin Books. pp. 63–100. ISBN 978-0-14-

044824-5.

3. Rinzler, Carol Ann (2009). The encyclopedia of cosmetic and plastic surgery. Facts on File

library of health and living. New York, NY: Facts On File. ISBN 978-0-8160-6285-

0.OCLC 223107099.

4.Dieffenbach, Johann Friedrich (1845). Die operative Chirurgie [The operative surgery] (in

German). Leipzig: FA Brockhaus. OCLC 162724901.

[page needed] cited by Tanzer, R. C.; Converse, J.

M.; Brent, B. (1977). “Deformities of the auricle”. In Converse, J. MD; Converse, John Marquis;

Littler, J. William (eds.). Reconstructive Plastic Surgery (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders. p.

1710. ISBN 978-0-7216-2682-6.

5.Naumann, Andreas (14 March 2008). “Otoplasty – techniques, characteristics and risks”. GMS

Current Topics in Otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery. 6: Doc04. ISSN 1865-1011. PMC

3199845. PMID 22073080.

6. Mustardé, J.C. (1963). “The correction of prominent ears using simple mattress sutures”.

British Journal of Plastic Surgery. 16: 170–8. doi:10.1016/S0007-1226(63)80100-9. PMID

13936895.

7. Merck, W.H. (2013). “Dr Merck’s stitch method. A closed minimally invasive procedure for

correction of protruding ears (Die Fadenmethode nach Dr. Merck. Ein geschlossenes, minimal-

invasives Verfahren zur Anlegung abstehender Ohren).” J Aesthet Chir, 6, 209-220.

8.Fritsch, M.H. (1995). “Incisionless Otoplasty”. Laryngoscope. 105, 1-11.

9.Fritsch, M.H. (2009) “Incisionless Otoplasty”. Otolaryngologic Clinics of North America

|volume=42 |issue=6 |pages=1199–208,10.Fritsch, M.H. (2004). “Incisionless Otoplasty”. Facial Plastic Surgery 20, 267–70

11.Stenström, Sten J. (1963). “A ‘natural’ technique for correction of congenitally prominent

ears”. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 32 (5): 509–18. doi:10.1097/00006534-196311000-

00003. PMID 14078273. S2CID 42807787.

12.Converse, John Marquis; Nigro, Anthony; Wilson, Frederick A.; Johnson, Norman (1955). “A

technique for surgical correction of lop ears”. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 15 (5): 411–8.

doi:10.1097/00006534-195505000-00004. PMID 14384519. S2CID 244781.

13.Chongchet, V. (1963). “A method of antihelix reconstruction”. British Journal of Plastic

Surgery. 16: 268–72. doi:10.1016/S0007-1226(63)80120-4. PMID 14042756.

14.Bisaccia, Emil; Lugo, Alexander; Johnson, Brad; Scarborough, Dwight (October 2004).

“Otoplasty: The Surgical Approach to Protuberant Ears”. The Dermatologist. 12 (10): 42.

15.Thorne 2007, p. 297.

16. Furnas, D. (1968). “Correction of prominent ears by concha mastoid sutures.” Plast Reconstr

Surg 42:189

17. Thorne 2007, p. 301.

18. Dubey, Punit (2025-02-10). “Otoplasty Surgery In Delhi”. Facial Plastic Surgery. Retrieved

2025-02-19.

19. Lindford, Andrew J; Hettiaratchy, Shehan; Schonauer, Fabrizio (2007). “Postpartum splinting

of ear deformities”. BMJ. 334 (7589): 366–8. doi:10.1136/bmj.39063.501377.BE. PMC 1800995.

PMID 17303887.